Interview by Malaya Velasquez

What is your AMMO?

Charles Saatchi exhibiting my work in London!

Artist, it’s a pretty loaded word and profession. If you could, describe your journey as an artist in a few words? Could you compare it to anything?

Maybe to the journey of a long distance marathon runner! I would say endurance and persistence is key.

What lead you to found the first photographic school in Benin?

I am now the founder and director of the first photographic school in Benin and recently have been appointed president of the Photographer’s Association of Porto-Novo. Not only this but I have been able to build a new three storey head quarters in the capital using the proceeds from my exhibitions with Jack Bell Gallery. Here I hope to use new technology to help train a younger generation of photographers.

What can you say is unique about the work being made at your school in Benin?

I would say that my students are making work in an environment that is changing shape at a very fast pace. While their art is still tied to cultural traditions it’s also very contemporary. I think this makes it particularly rich work.

You’ve seen some success thus far; would you say you are pleased with it?

I first met Jack Bell when he came to West Africa in 2010 on a field trip to Benin. He was taken with my work immediately and also liked the idea that I still work on film with a medium format camera. Since we met, I have had four solo exhibitions with Jack Bell Gallery in London. The museum interest has been fantastic. The Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford, the Kelvingrove Art Gallery & Museum, Glasgow, and the Museum of Modern Art Equatorial Guinea have acquired my work.

Well known private collectors have been buying my works from Jack also. Charles Saatchi in London and Jean Pigozzi in Geneva have been big supporters for me. Last year I showed works in ‘Out of Focus’, a group exhibition at the Saatchi Gallery. They published a full color catalogue including my works among some brilliant contemporary artists from around the world. Soon after I had my works shown at Paris Photo in Paris. For me, it’s amazing to see this progress in such a short period of time. It’s true that the work I am making is very African, but it’s also great art in a contemporary sense and it seems there is very ready market for this in Europe and America. I think that so many big collectors and museums have bought my work would confirm this.

How would you define success as an artist, does it exist?

I’m not sure it exists; I am always striving for the next level. I would say that I take pleasure in being able to communicate to a wide international audience about where I’m from.

What do you see your next project to be?

I’m currently working over the border in Nigeria around themes of consumption.

Are there any upcoming projects you are particularly excited in working on?

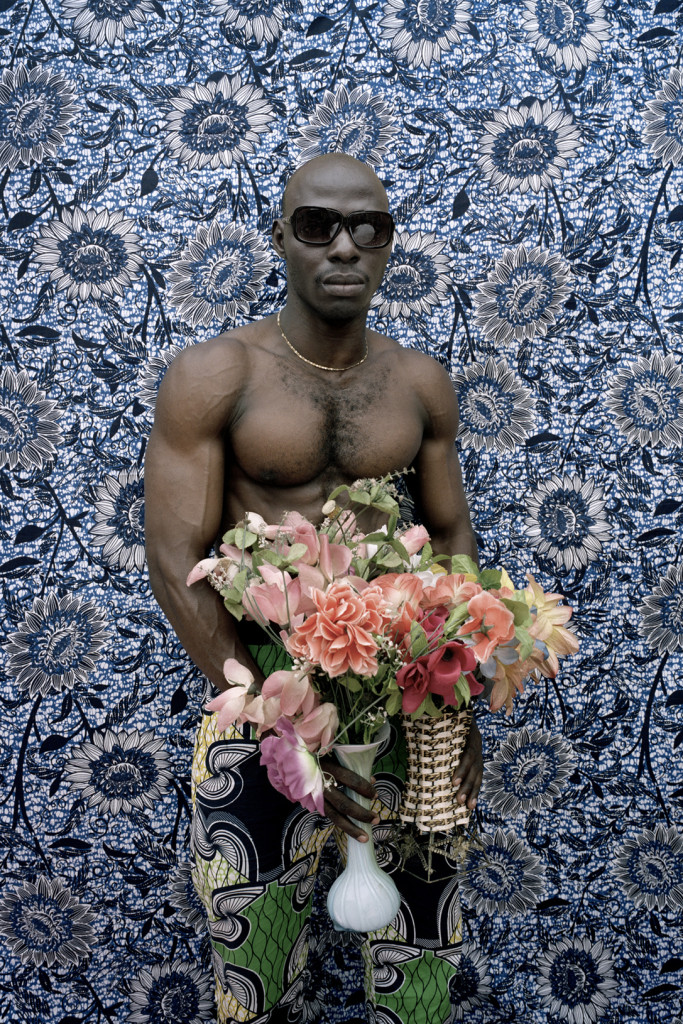

My ongoing portraiture project, entitled ‘Citizens of Porto-Novo,’ captures the people of Benin’s capital and has been taking shape over about 4 years now. The main reason I started this project is because Porto-Novo is an extremely interesting environment and in a way, my studio has become a crossroads for the city’s diverse population. Porto-Novo has had a complicated past with slavery, colonialism, vodun and missionaries, and today it’s people bear the marks of all of these. I am documenting the history of my people. My subjects vary from simply people in the streets to more structured portrait shots in the studio.

What was your experience, exposure to art growing up? Can you describe the experience being trained by your father as a photographer?

I come from a very traditional photographic background and I grew up surrounded by cameras. My father had earned himself a reputation as one of West Africa’s most renowned studio photographers. This generation of African photographers gained their knowledge of photography while fighting for the French in World War II and returned to set up local photographic studios.

As far back as I can remember, I would always be spending evenings in my father’s studio. He would work late into the night printing and developing exquisitely crafted photographs in his makeshift darkroom. I would sit on the floor observing, fascinated by the enlarger and the countless negatives.

Does any singular moment of that process standout from the others?

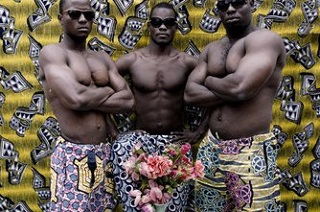

As I grew older I became my father’s assistant and we would travel miles together by bicycle or moped to far – flung villages. There we would work towards recording the most important moments in the lives of the local inhabitants. Studio photography has been a West African tradition since the late fifties and early sixties. As a youngster with my father we would put together outdoor studios using painted backgrounds and local textiles where clients would pose and show off. Fashion, costume and props like plastic flowers are very common in West Africa, and have always been used in the traditional studios to show style and taste.

To what degree would you say your work is self-reflexive?

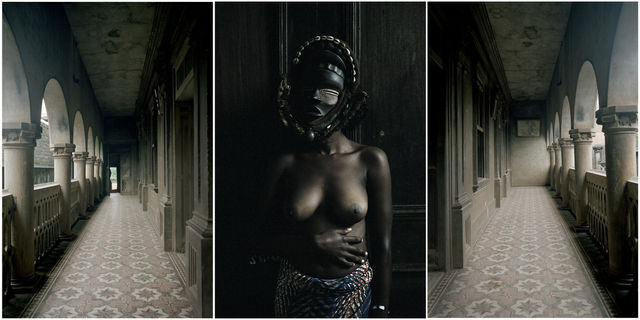

Portrait photography in Benin has always had a split role. On the one hand it has been about making images of a young urban population keen to establish the modernity of their lives. Yet on a deeper level, the portraits record a people caught between tradition and progress – a pre-colonial past and post-colonial future. In a local sense, photography is marked by deep mysticism and dark dramas. Images of ju-ju men and vodun priests and priestesses are popular subjects and photography plays a role not just in life, but in your afterlife. It is a commonly held belief, and source of fear, in Benin’s culture that a person’s soul lives on, trapped, within the photograph.

In this part of the world – with its mixed spiritual traditions of Catholicism and vodun (the official religion of Benin) – the photograph exist as a way to mediate between the living and the dead. In my work, I want to draw on these deep artistic traditions to give my portraits a sense of timelessness and an element of the supernatural. I have grown up among these traditions, and I want my photographs to resonate with the cultural understanding of an insider.